|

|

|

|

PLEASE! If you see any mistakes, I'm 100% sure that I have wrongly identified some birds.

So please let me know on my guestbook at the bottom of the page

So please let me know on my guestbook at the bottom of the page

The Ural Owl (Strix uralensis) called Slaguggla in Skåne, is a large nocturnal owl. It is a member of the true owl family, Strigidae. The Ural Owl is a member of the genus Strix, that is also the origin of the family’s name under Linnaean taxonomy. Both its common name and scientific name refer to the Ural Mountains of Russia where the type specimen was collected. However, this species has an extremely broad distribution that extends as far west as much of Scandinavia, montane eastern Europe, and, sporadically, central Europe, thence sweeping across the Palearctic broadly through Russia to as far east as Sakhalin and throughout Japan. The Ural Owl may include up to 15 subspecies, but most likely the number may be slightly fewer if accounting for clinal variations. This forest owl is typical associated with the vast taiga forest in Eurosiberia, although it ranges to other forest types, including mixed forests and temperate deciduous forest. The Ural Owl is something of a dietary generalist like many members of the Strix genus, but it is usually locally reliant on small mammals, especially small rodents such as voles. In terms of its reproductive habits, Ural Owls tend to vigorously protect a set territory on which they have historically nested on a variety of natural nest sites, including tree cavities and stumps and nests originally built by other birds but now, in many parts of the range are adapted to nest boxes made by biologists and conservationists. Breeding success is often strongly correlated with prey populations. The Ural Owl is considered to be a stable bird species overall, with a conservation status per the IUCN as a least concern species. Despite some local decreases and extinctions, the Ural Owl has been aided in central Europe by reintroductions. Distribution The Ural Owl has a large distribution. In mainland Europe, its modern distribution is quite spotty, with the species being found in central Europe in southeastern Germany, central and eastern areas of the Czech Republic, southern Austria, all but western Slovenia, and spottily but broadly in several areas of western, southern and northeastern Poland. The distribution in Germany is particularly nebulous (and perhaps aided by reintroductions branching from the well-known Bavarian population), with evidence of Ural Owls apparently residing (and possibly nesting) considerably away from currently known haunts in Egge far to the west and mysteriously turning up rather to the north in Harz and Lüneburg Heath. In eastern Europe, the species is found in eastern Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, western Serbia, montane west-central Bulgaria, montane central Romania, much of Slovakia, southwestern Ukraine, southern and eastern Lithuania, northern Belarus, eastern Latvia and much of Estonia. In Scandinavia, its distribution is quite broad, though it is only found in southeastern part of Norway, as Ural Owls may be found ranging across most of Sweden and Finland but is absent from the northern stretches as well as southern Sweden (largely the peninsular area). Its range in Russia is extensive but it is absent from areas where habitat is not favorable. In western and European Russia, it is found as far south roughly as the Bryansk, Moscow and northern Samara north continuously to Kaliningrad, the southern part of the Kola Peninsula and Arkhangelsk. In the eponymous Ural region, it is found from roughly Komi south to Kamensk-Uralsky. In the general area of Siberia, the Ural Owl is found widely discontinuing its typical range in the foothills of the Altai Mountains to the west and being found north roughly as far as Batagay in the east. The species’ distribution is continuous to the Russian Far East to as far as Okhotsk Coast and Magadan, Khabarovsk Krai and Sakhalin Out of Russia, the range of the Ural Owl continues into northeastern Mongolia, Northeastern China inland nearly as far as Beijing and down to Shandong and throughout the Korean Peninsula. The Ural Owl is also distributed through all five of the main islands of Japan (i.e. only absent from Okinawa/Ryukyu Islands to the south). Vagrancy has been reported in Europe and Russia, which may account for sightings of the species almost throughout Germany. Furthermore, as many 16 records exist of the species turning until in northern Italy. Strix uralansis -Range Map - Click MAP for full size map

By Ulrich prokop - Self-made by author, based on Claus König @ Friedhelm Weick: Owls of the World. Helm, London, 2008;

S. 381Mapsource: File:A large blank world map with oceans marked in blue. PNG, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=8427335 Habitat Ural Owls tend to occur in mature but not too dense primary forest, which can variously be in coniferous, mixed or deciduous areas. Normally, they prefer to be close to an opening. These are often compromised by forest bogs with wet ground underfoot is overgrown by a mixture of spruce, alder and/or birch or by damp heathland with scattered trees. Predominant trees in much of the range are often spruce, fir and pine forests in north and alder, beech and birch with mixtures of the above conifers in the south. Quite often they are adapted to high elevation forest in mountains, but in remote wildlands they can adapt equally well to areas down to sea level. In the Carpathian mountains, they tend to favor almost exclusively beech-dominated forests, normally at elevations of 250 to 450 m above sea level. Forest characteristics of these beech-dominated woods showed that during forest management showed they need at least 100 ha of woods to persist, with parts of the forests needing to be at least 45-60 years old. Carpathian Ural Owls typically occur far from human habitations and woodland edge not surrounded by forest and typically avoid parts of the forest with steep slopes or with dense undergrowth. Carpathian birds often preferred areas with glades that bear gaps between the trees often around 25 m or so and usually with plentiful broken trees. Young, post-dispersal owls in the Carpathians birds show less strong habitat preferences and may utilized wooded corridors that often are connected to remaining ideal habitat areas. Reportedly the countries of Slovakia, Slovenia then Romania have the most extensive ideal habitat in the Carpathians and resultingly have the highest local densities of Ural Owls, perhaps in all of Europe. Forest predominant in beech were also seemingly preferred by the reintroduced Ural Owls in Bavarian Forest, again with old growth preferred with plentiful sun exposure. Bavarian owls occurred in areas that were also often rich in large mammals since their preference for access to parts of the forest with broken trees and openings often coincided. Further north in Latvia, forests inhabited were usually far older than was prevalent in the regional environment, usually with a preference for forest areas with trees at least 80 years old. Finnish populations apparently most often occur in spruce dominated forest, usually having discreetly segregated forest preferences apart from sympatric species of owls except for the boreal owl, which also preferred spruce areas but occurred more regularly when the dominant Ural Owls are scarce. In the taiga of western Finland, it was found that biodiversity was consistently higher in the vicinity of Ural Owl nests than outside these vicinities, rendering the Ural Owl as perhaps a “keystone species” for the local ecosystem. Riverine forests with birch and poplar are often utilized in the taiga as well as spruce or fir forests (montane taiga) in the Ussuri river area. Generally in northern climes such as Finland and western Russia, wherein the Lapland area the Ural Owl is likely to reach the northernmost part of its range, it is adaptive to Subarctic areas possibly up to the tree line but does not adapt as well as the Great Grey Owl to areas of dwarf forest just south of the tundra, generally needing taller, more mature forests to the south of this. Historically, they normally occur in remote, little disturbed areas far from human habitations. The Ural Owl is largely restricted from areas where forest fragmentation has occurred or park-like settings are predominant, as opposed to the smaller, more adaptive tawny owl which acclimates favorably to such areas. On the contrary, in some peri-urbanized areas of Russia, such as the metropolitan parks and gardens so long as habitat is favorable and encouraging of prey populations, the Ural Owl has been known to successfully occur. Some towns and cities whose region hold some populations of Ural Owls are Chkalov, Kirov, Barnaul, Krasnoyarsk and Irkutsk, and even sometimes Leningrad and Moscow. Changes in nesting habits due to the erection of nest boxes has almost allowed Ural Owls to nest unusually close to human habitations in the western part of the range, especially in Finland. An exceptional record of synanthropization in this species for Europe was recorded in Košice, Slovakia where a 10-15 year apparent increase of an unknown number of owls have been observed between the months of November and June. At least one Ural Owl was recorded to habituate the city of Ljubljana in Slovenia but there was no evidence it was able to breed or establish a territory given the limited nature of woodlands in the vicinity.   Range map from www.oiseaux.net - Ornithological Portal Oiseaux.net

www.oiseaux.net is one of those MUST visit pages if you're in to bird watching. You can find just about everything there

Taxonomy The Ural Owl was named by Peter Simon Pallas in 1771 as Strix uralensis, due to the type specimen having been collected in the Ural mountains range. While the Urals fall around the middle of the species’ distribution, some authors such as Karel Voous lamented that a more broadly appropriate than Ural Owl wasn’t derived for the English common name. In other languages, the species is referred to as Slaguggla, or “attacking owl”, in Swedish, Habichtskauz, or “goshawk-owl”, in German or as the “long-tailed owl” in Russian. The Ural Owl is a member of the Strix genus, which are quite often referred to as wood owls. Conservatively, about 18 species are currently represented in this genus, typically being medium to large sized owls, characteristically round-headed and lacking ear tufts, which acclimate to living in forested parts of various climatic zones. Four owls native to the neotropics are sometimes additionally included with the Strix genus but some authorities have also included these in a separate but related genus, Ciccaba. Strix owls have an extensive fossil record and have long been widely distributed. The genetic relationship of true owls is somewhat muddled and different genetic testings has variously indicated that Strix owls are related to disparate appearing genera like Pulsatrix, Bubo and Asio. The tawny owl is thought to be a close relative of the Ural Owl. Authors have hypothesized that the origin of the species divide followed Pleistocene continental glaciations segregated a southwest or southern group in temperate forest (i.e. the tawny) from an eastern one inhabiting cold, boreal ranges (i.e. the Ural). The species pattern is mirrored in other bird species, i.e. the European green woodpecker (Picus viridus) from the more northern transcontinental grey-headed woodpecker (Picus canus). After retreat of the continental ice masses, the ranges more recently penetrated each other. While the life history details of the tawny and Ural Owls are largely corresponding, nonetheless the species have a number of morphological differences and are largely adapted to different climates, times of activity and habitats. Based on Strix fossil species from Middle Pleistocene (given the name Strix intermedia) in variously the Czech Republic, Austria and Hungary show from leg and wing bones indicate an animal of intermediate form and size between Ural and tawny owls. However, fossils of a larger and differently proportioned Strix owl than a tawny owl, identified as Strix brevis, from Germany and Hungary from before the Pleistocene (i.e. Piacenzian) and as well as diagnosed Ural Owl fossils from disparate southerly deposits in Sardinia from the Early Pleistocene and in Middle Pleistocene deposits in the Pannonian Basin as well as much later during the early Holocene from far to the west in Belgium, France and Switzerland suggest a more complicated evolutionary and distributional history. A hybrid was recorded in captivity between a male Ural and a female tawny owl, which managed to produce two offspring that were intermediate in size and had a more complex song that was also shared some characteristics with both species’ vocalizations. Some species in America, such as namely the barred owl, are at times thought to be so closely related as well to the extreme that the Ural and barred and spotted owls (Strix occidentalis), have been considered to potentially be part of a species complex or even within the same species. However, there is no evidence nor likelihood that the Strix owls between America and Eurasia ever formed a continuous population given their adaptation to well-forested areas as well as the fact that the barred owl is more ecologically similar to the more generalized tawny owl, despite being of intermediate size between tawny and Ural Owls (closer in size to the latter), and that the tawny does not range anywhere close to the boundary between North America and Russia as does the Ural. Certainly the most ambiguous aspect of the relations of Ural Owl is the Père David's owl which has both historically and currently been considered either an isolated subspecies of the Ural Owl or a distinct species. It is thought that the Père David's is likely a glacial relict of the mountainous forest of western China where plant and animal life often remain reminiscent of pre-glacial life. Recent study has indicated that the Père David's owl is valid species based on appearance, voice, and life history differences, though genetic studies have shown a somewhat muddled diversity between races of the Ural Owls species complex. It has been recognized by The Clements Checklist of Birds of the World but BirdLife International and IUCN still classify it as a subspecies of the Ural Owl. Subspecies This is a polytypic species; eight subspecies are recognized. • S. u. liturata: Northern Europe to north-western Russia, northern Poland, Belarus and middle Volga • S. u. uralensis: Eastern European Russia to Sea of Okhotsk • S. u. macroura: Carpathian Mountains to Bulgaria and western Balkans • S. u. yenisseensis: Central Siberian plateau • S. u. nikolskii: Transbaikalia to Sakhalin, north-eastern China and Korea • S. u. japonica: Hokkaido (northern Japan) • S. u. hondoensis: Northern and central Honshu (Japan) • S. u. fuscescens: Southern Honshu south to Kyushu (Japan) Description Like most Strix species, it has a broad, rounded head with a correspondingly round facial disc, barring a tiny V-shaped indentation. The Ural Owl has, for an owl, an exceptionally long tail that bears a wedge-shaped tip. In colour, it tends to be a plain pale greyish-brown to whitish overall (with more detailed description of their variation under subspecies), with a slightly darker grey-brown to brown back and mantle with contrasting whitish markings. The underparts are pale cream-ochre to grey-brown and are boldly (though sometimes more subtly) overlaid with dark brown streaking, without crossbars. Many variations are known in overall plumage colour both at the subspecies level and the individual level. However, the Ural Owl usually appears as a rather pale grey-brown owl, usually lacking in the warmer, richer colour tones of many other Strix owls, with distinct streaking below. In flight, an Ural Owl shows a largely buffish-white underwing marked with heavy dark bars around the trailing edge and tip, while the long white tipped tail often appears slung downwards. Their flight style is reminiscent of a buzzard but with deeper, more relaxed wing beats, with their style of flight often giving the appearance of quite a large bird. The eyes are dark brown, being relatively small and closely set to each other, which is opined to give them a less “fierce” countenance than that of a Great Grey Owl (Strix nebulosa). The eyes are reminiscent of an almond in both shape and colour. The bill is yellowish in colour, with a dirty yellow cere. Meanwhile, the tarsi and toes are covered in greyish feathering and the talons are yellowish brown with darker tips. The Ural Owl is a rather large species. Full-grown specimens range in total length from 50 to 64 cm, which may render them as roughly the eight longest owl species in the world (though many owls are heavier on average). Wingspan can vary in the species from 110 to 134 cm. Like most birds of prey, the Ural Owl displays reverse sexual dimorphism in size, with the female averaging slightly larger than the male. Reportedly talon size and body mass is the best way to distinguish the two sexes of Ural Owl other than behavioral dichotomy based on observations in Finland. Weight is variable through the European part of the range. Males have been known to weigh from 451 to 1,050 g and females have been known to weigh from 569 to 1,454 g Voous estimated the typical weight of males and females at 720 g and 870 g, respectively. It is one of the larger species in the Strix genus, being about 25% smaller overall than the Great Grey Owl, the latter certainly being the largest of extant Strix species in every method of measurement. Body masses reported for some of the more southerly Asian species such as brown wood owl (Strix leptogrammica) and spotted wood owl (Strix selopato) (as well as the similarly sized but unweighed mottled wood owl (Strix ocellata)) show that they broadly overlap in body mass with the Ural Owl or are even somewhat heavier typically despite being somewhat smaller in length. Despite having no published weights for adults, Père David's owl (Strix davidi) seems to also be of a similar size to the Ural Owl as well. Among standard measurements, in both sexes, wing chord can measure from 267 to 400 mm across the range and tail length can from 201 to 320 mm. Among extant owls, only the Great Grey Owl is certain to have a longer tail. Though less frequently measured, the tarsus may range from 44 to 58.5 mm and, in northern Europe, the total bill length measured from 38 to 45 mm (1.5 to 1.8 in). The foot span can regularly reach around 14.3 cm in full-grown owls.

Vocalizations and ear morphology The song of the male is a deep rhythmic series of notes with a short pause after the first two notes, variously transcribed as wihu huw-huhuwo or huow-huow-huow. The phrase repeats at intervals of several seconds. The male’s song may carry up to 2 km to human perception but usually is considered not quite that far-carrying. Peak singing times in Finland during springtime are 10 pm-12 am and more intensely at 1-3 am, which differed from the peak times for nest visits. The female has a similar but hoarser and slightly higher pitched song, giving it a more "barking" quality. Not infrequently, Ural Owls will duet during courtship. In addition, a deep, hoarse heron-like kuwat or korrwick is probably used as a contact call. These are more elongated and harsher than the kewick note made by tawny owls (Strix aluco). Young beg with hoarse chrrreh calls, again similar to the ones by young tawny owls but deeper. Vocal behavior tends to peak in early spring until the young leave the nest, most often during incubation and nesting in the form of prey delivery countercalling. The alarm call, which is typically delivered during territorial rounds, of the male is coincidentally analogous to the territorial song of the short-eared owl (Asio flammeus), which is considered a somewhat hollow sounding hoot. The alarm call is audible at up to 1,500 m away. The Ural Owl also has a particularly menacing bill-snapping display. In total, Swedish biologist reported that about nine different calls were uttered by Ural Owls. Despite the range of calls, the species is generally very quiet for a large owl and may not vocalize even at peak times for perhaps up to nearly 2 days. The ears of the Ural Owl are quite large, averaging about 24 mm on the left and 27 mm on the right with the pre-aural dermal flap measuring about 13 mm. In fact their ears are amongst the largest recorded in owls. In combination with their large ears, the well-developed facial disc shows the importance of sound to hunting to this and other owl who hunt in boreal zones. While the Ural Owl was found to be aurally overdeveloped compared to other Strix such as the barred owl (Strix varia) it was found to be underdeveloped in comparison to owls more confined to true boreal type habitats, like the Great Grey Owl and the boreal owl (Aegolius funereus). Listen to the Ural Owl

Sound from www.xeno-canto.org

Sound from www.xeno-canto.org

Sound from www.xeno-canto.org

Sound from www.xeno-canto.org

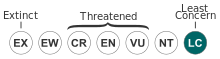

Confusion species The Ural Owl is a fairly distinctive looking bird but can be confused for other owls, especially with others in the Strix genus. The tawny owl is much smaller with a conspicuously shorter tail and a relatively larger head. The tawny species, which occurs variously in grey, brown and red morphs, has underparts with dark shaft-streaks and crossbars, as opposed to the heavy but straight streaking of the Ural Owl. The Great Grey Owl is larger than the Ural Owl with a huge head and relatively even smaller yellow eyes while their facial disc has strong concentric lines. In colour, the great grey is distinctly more solidly uniform and somewhat dark greyish than the Ural Owl. An unlikely species to mistake a Ural Owl is the Eurasian eagle-owl (Bubo bubo) which is much larger (by a considerable margin the heaviest and longest winged owl in Europe) with prominent ear tufts, a squarish (not rounded) head shape and orange eyes as well as with distinctly different markings. Long-eared owls (Asio otus) are much smaller and slimmer, with prominent ear-tufts, orange eyes and more prominent dark markings. More similar than any in Europe, the closely related Père David's owl does not occur in the same range as (other?) Ural Owls but is darker in plumage, also with a facial disc marked with darker concentric lines. Due to its partially diurnal behaviour during warmer months, some authors consider it confusable with the very different looking (but similarly largish and long-tailed) northern goshawk (Accipiter gentilis). Behaviour The Ural owl is often considered nocturnal with peaks of activity at dusk and just before dawn. However, taken as a whole and since it mainly lives the taiga zone where very long summer days are the norm against extensive dark during the winter, Ural owls are not infrequently fully active during daylight hours during the warmer months, while brooding young. Presumably during winter, they are mostly active during the night. Thus, the species may be more correctly classified as cathemeral as is much of their main prey. The wide range of activity times, and partial adaption to daytime activity, is further indicated by the relatively small eyes that the species possesses. This contrasts strongly with the tawny owl, which almost always fully nocturnal. During the day, Ural owls may take rests on a roost, which is most typically a branch close to trunk of a tree or in dense foliage. Normally, Ural owls are not too shy and may be approached quite closely. Historically, European birdwatchers often consider the species to be rather elusive and hard to observe. However, as the species as acclimated to nest boxes closer to areas where humans frequent, especially in Fennoscandia, encounters have increased sharply. Territoriality and movements The Ural owl is a highly territorial and residential species that, as a rule, tends to stay on the same home range throughout the year. While most boreal owls, such as great grey owl and boreal owl, are generally given to nomadism and irruptive movements, with nearly the entire population following the population cycle of their primary prey, the Ural owl rarely departs from its home range even when prey populations decrease. Apart from the great grey species, like the Ural, most species in the Strix genus of owls are both highly territorial and non-migratory. Territories are generally maintained with songs, most often uttered by the male of the resident pair. This is quite the norm for owls in almost every part of the world. Due probably to its natural scarcity, very few firsthand accounts are known of territorial fights between adults but they presumably occur as Ural owls can be quite aggressive owls (or are at least in the context of protecting their nests). However, according to a study in southern Poland, Ural owls are generally less aggressive in the non-breeding seasons than are tawny owls to other owls and may be slightly tolerant of smaller owl species on their home range while the tawny is less so. That the Ural is slightly less aggressively territorial than the tawny owl is also supported in a study from Slovenia when tawnys had more spirited calls to recorded calls and launched more aggressive attacks to the taxidermed specimens of Ural, boreal and owls of their own species than did the Ural owls to any of the same stated stimuli. As for movements, as opposed to the sedentary adults, immatures may wander distances of up to about 150 km. An occasional individual may wander straggle even further and remain for some time in a wintering area. A small number of straggling young Ural owls may occur irregularly down in southeastern Europe outside of the typical range of the species. Some circumstantial evidence was reported of Ural owls moving downhill in mountains in Japan when snowfall was heavy. Siberian population shows somewhat southward movements in severe winters, as the number of prey animals plummets and the owls themselves face risk of freezing. Status The Ural Owl is not a densely populated bird but can be locally not uncommon. The IUCN estimates that there are between 350,000 and 1,200,000 individuals living in the wild globally. Most decreases in recent history have been reported from areas where hollow and broken trees were removed from forests. In Estonia, managed forest almost invariably have fewer Ural Owls than undisturbed forest has because of reduction of snags and other natural cavities to use. However, the general trends are positive for most European Ural Owl populations. The erection of nest boxes has caused population increases in several parts of the range, especially Finland. In eastern Europe, it is one of the more stable owl species, though it is far less numerous overall than some (i.e. tawny, long-eared, and little owls (Athene noctua)). Several population increase and expansions have been detected in central and eastern Europe for Ural Owls in recent history, in sync with other owls considered boreal species (i.e. great grey, boreal, Eurasian pygmy). Previous records indicated staple populations in the 1980s for Ural Owls in the western Carpathian mountains (estimated at about 1000 pairs) and northern Belarus (at 50-100 pairs). By the 1990s, the number had grown to 1000-1500 pairs in the western Carpathians and to 220-1350 pairs in northern Belarus. By 2005, the numbers were up to 3500 pairs in Carpathians and a drastic increase to 2700-4300 pairs in Belarus. In the Czech Republic, partially due to deliberate reintroductions, the numbers went from 1-5 pairs in 1985-89 to 25-40 pairs by 2001-2003. In selected plots of southeastern Poland, Belarus and Latvia, densities went from 1-2 pairs per 100 km2 to 10 pairs per 100 km2. In these three countries, northern population now much higher density than southern ones, i.e. 5-8.1 pairs per 100 km2 (39 sq mi) in north to 3.1-3.6 pairs per 100 km2 in the south. A range expansion of Ural Owls was detected in western Ukraine (in the general region of Roztochya Biosphere Reserve and Yavorivskyi National Park). In 2005-07 up to 1.7-2 pair per 10 km2 whereas in the past (i.e. to the 1990s) the species was a rare vagrant to this area. This density of this Ukrainian population is higher than seemingly most in Scandinavia and Belarus but lower than in southwestern Poland and Slovenia; while whether this represents a population increase or merely a population shift is unknown nor its relation to forestry. In some parts of Slovakia, such as Slanské vrchy, Vihorlat and the Ondavská Highlands the density of pairs may be up to a pair per square kilometer, perhaps the highest known specieswide. 400-500 Slovenian pairs from 1973-1994 is as of 2006 is estimated at 1400-2500 pairs. In the Orava region of Slovakia, the population may have increased fivefold during the above stated years. While many owl species (eagle-owl, long-eared, boreal) have appeared to have generally declined in period of 1982-2007 in Finland, to the contrary Ural Owls increased by about 1% (excluded from these estimates were too difficult to analyze northerly nomadic owl species). In every regard but number of nestlings that were ringed (in which it also trails the Eurasian pygmy), it has been observed the Ural is the 2nd commonest detected breeding owl after the boreal owl in Finland with 2545 territories found, 1786 nests observed and 4722 nestlings ringed. An increase of the population was found in the Moscow region where tall stands remained despite the rather developed environment nearby. Occasionally, Ural Owls are vulnerable to flying into manmade objects. In most parts of the range, they are less vulnerable than many other large birds of prey (in part because of their preference for remote forests) but certainly a few are likely to be claimed as such. Many such mortalities are due to wire collisions and electrocutions, which are likely increase especially as populations expand and move into areas closer to human habitations. Other collision kills, such as with glass buildings and, widely, with various automobiles, may too potentially be on the increase. Though historically subject to some degree of persecution, Ural Owls were spared from the worst of it perhaps by nesting in remote forests and possibly by being generally less predatory to small domestic fowl, game animals and the like than large raptorial birds like Eurasian eagle-owls, Golden Eagles and northern goshawks, all of which were badly persecuted and thusly reduced. Like other wild birds, Ural Owls may be vulnerable to some degree of mortality due to diseases and infections but these are unlikely to compromise overall populations. A case of the bacterial infectious disease Tularemia was observed in an Ural Owl as was Usutu virus in a single bird. 71.4% of 14 wild Ural Owls in Japan had blood parasites while a smaller but still present number of Acanthocephala and roundworms were detected in known European data. Many Japanese Ural Owls were also found to be vulnerable to biting lice. Reintroduction Species reintroductions have been undertaken in some different parts of Europe. By far the best documented Ural Owl reintroduction was in the Bohemian forest, which ranges between the countries and regions of Bavaria in Germany, the Czech Republic and upper Austria. Previously the species was extinct here by 1926 (by 1910 on the Austrian side). Established of captive breeding stock occurred between 1972 and 2005 (with origins from 7 different countries and a mixture of the two main European subspecies). For this breeding program, 212 young Ural Owls were originally released. During the study, experimental introductions were made to tawny owl nests, although this potentially exposed them to risk of hybridization. Otherwise, parentage consisted of relatively newly established Ural Owls. Both tawny and Ural Owls were shown to be able to successfully raise the young Ural broods. Food was also offered to pairs at nearby release pens and 60 nest boxes erected to compensate for lack of nest sites, especially in areas of secondary forest. 33 Ural Owls were recovered dead, while an additional 4 were weakened or injured to the state of being unable to continue to live in the wild. Most of the mortality was due to electrocution or were hit by cars but a few were illegally shot. The first wild breeding of an Ural pair in the Bohemian forest occurred in 1985 but the first successful breeding was not until 1989 (with the pair having producing 4 offspring) Between 1981 and 2005 a total of 49 broods were recorded, 31 of which were successful with 59 young produced (avg 1.3 per all attempts, 1.9 per successful pair). No fewer than 6 pairs (possibly 5-10 breeding pairs) were established by the end of study, with the carrying capacity within the forest estimated at 10 pairs. For a self-sustaining breeding population, it was felt that at least 30 pairs are necessary in the general area within connected corridors to the Bohemian forest. Therefore, 87 birds were introduced into nearby Sumava National Park between 1995 and 2006, an estimated 2-3 breeding pairs have established there now. A still uncertain pilot program in Mühlviertel, Austria may or may not have produced a pair as well. In 2001, among two reintroduction attempts in Austria, both failed. All told from the entire Bavarian reintroduction, it was said that the owls producing a total of 204 offspring between 1972 and 2014, although many of these may not have survived. More successful than the Austrian part of the Bavarian forest reintroductions was the reintroduction elsewhere in Austria, namely the Vienna Woods. In this project, 67 young owls were released between 2009 and 2013. A nesting box network of 127 boxes were set out to be utilized and one of Europe's largest stands of beech trees was present. In the Vienna Woods, the survival rate was high at about 70.5%. By 2011-2012, 10 pairs attempted to nest, establishing home ranges averaging about 300 ha and produced 3.1 fledglings per successful pair. Conservation status

Least Concern (IUCN 3.1)

IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2013. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Sighted: (Date of first photo that I could use) 15 April 2021 Location: eBird hotspot: Skillberg, Fläckebo  Ural Owl / Slaguggla

15 April 2021 - eBird hotspot: Skillberg, Fläckebo  Ural Owl / Slaguggla

15 April 2021 - eBird hotspot: Skillberg, Fläckebo  Ural Owl / Slaguggla

15 April 2021 - eBird hotspot: Skillberg, Fläckebo PLEASE! If I have made any mistakes identifying any bird, PLEASE let me know on my guestbook  You are visitor no.

To www.aladdin.st since December 2005

|

|